Dicamba will show us the promise--and limitations--of big data in 2017

/You would have to live under a rock to not have heard about farmers’ issues with dicamba this growing season. Arkansas banned the pesticide, Missouri temporarily banned and then changed the label, and complaints are skyrocketing in Indiana and Illinois.

For a discussion of the problems, check out Illinois farmer Jeremy Wolf’s descriptions of the problems on his non-dicamba-tolerant soybeans in the heart of central Illinois. If this isn't enough, read University of Missouri's article: "Ag Industry, do we have a problem yet?"

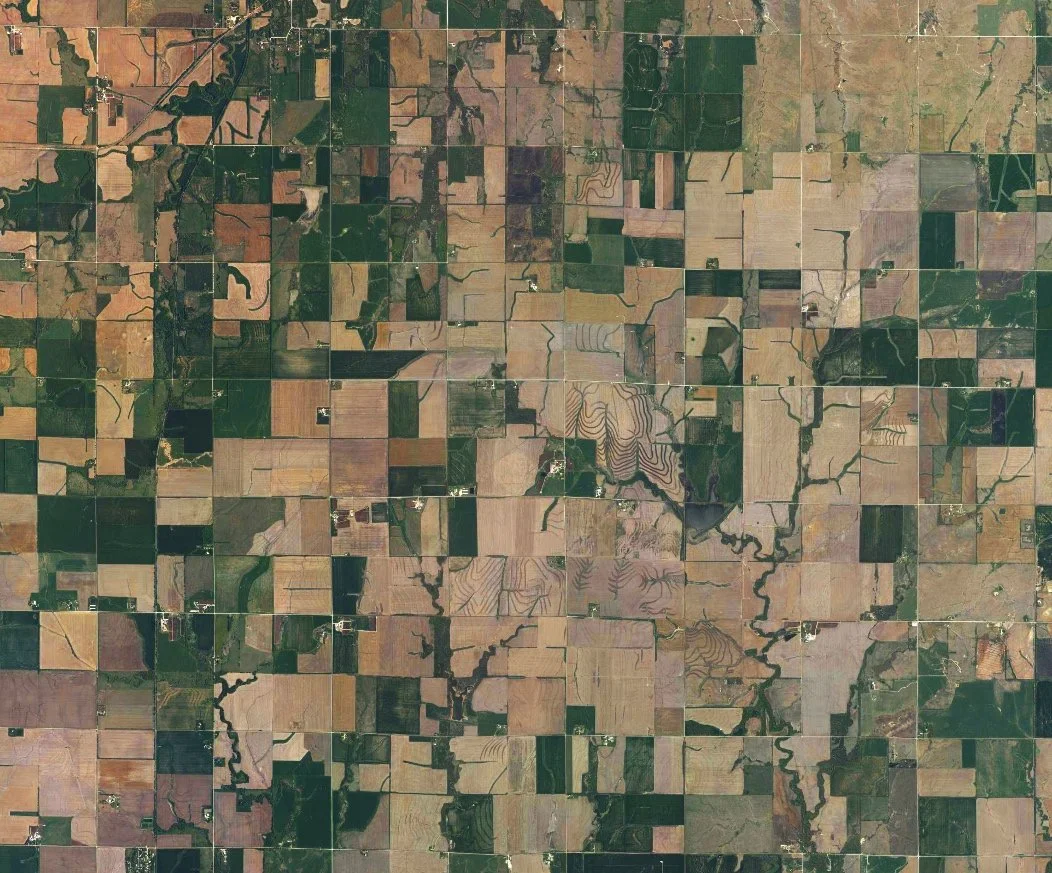

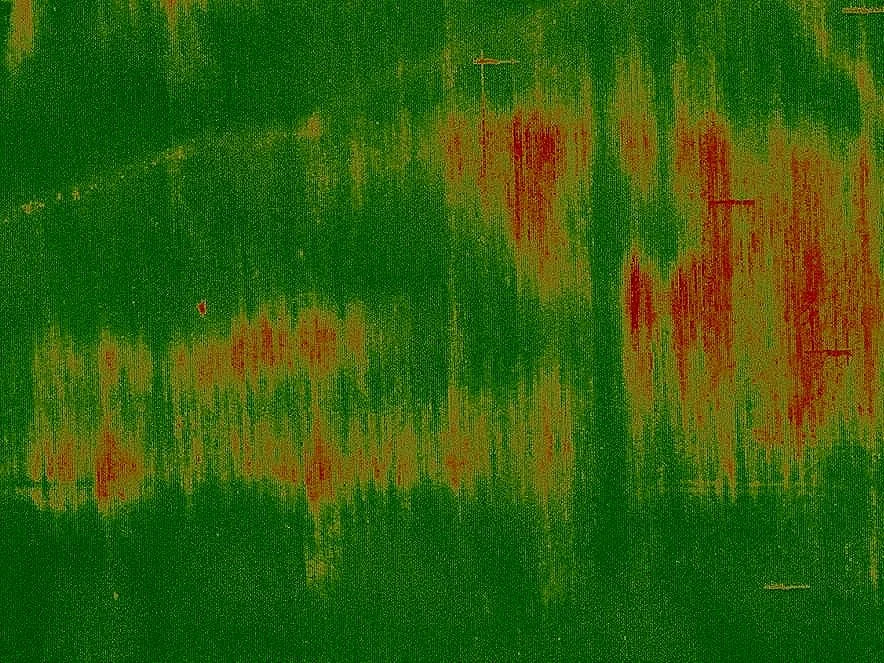

Farmer Jeremy Wolf's before (bottom) and after (top) pictures of one field suspected of dicamba damage.

Monsanto and BASF’s public relations teams have been working in overdrive to contain the fallout. Read Monsanto's Robb Fraley’s list of reasons why he believes Monsanto is not to blame. However, he later took a more conciliatory approach and explained "We are taking these reports extremely seriously."

Federal crop insurers, who usually come to farmers’ rescue when faced with crop damage, have been quick to point out that crop insurance policies do not cover dicamba drift. The USDA started its owned FAQ page just for this reason, explaining "chemical damage caused by improper application by a producer or inadvertently through a third party" is not a covered loss.

No one want really wants to take responsibility for the issues, so who is going to pay for losses when this is all said and done? For the first time in history, I think ag data is going show us who is responsible, but also tell us the limitations on what we can learn from data in 2017.

In the past, sorting out who caused the widespread damage we see today would be nearly impossible. But the collecting, storing, and using ag data will change that. Monsanto’s Climate Corporation likely has a very detailed database of dicamba sprayings (from its users). In fact, Robb Fraley tells farmers in his most recent letter to contact the Climate Corporation to "help understand whether unusual environmental conditions or weather patterns might have affected applications this season." Ag retailers too have precise records of when and where their applicators sprayed dicamba in 2017, as well as detailed weather data. Thus, in many cases, figuring out who caused dicamba damage will not be as impossible as people think.

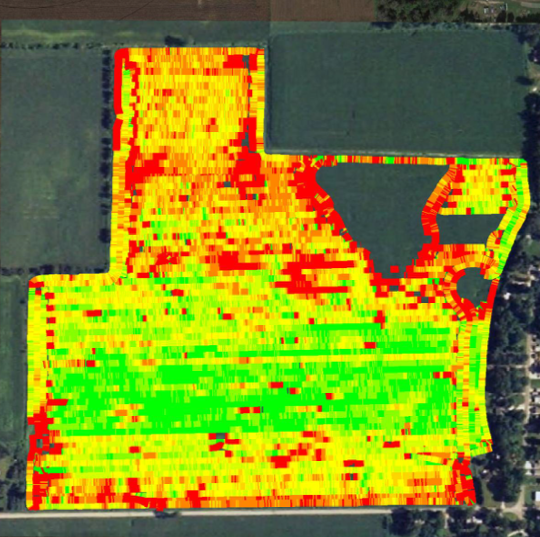

Off-target chemical application can produce strange patterns in fields. Some areas are not damaged, some are very damaged, and some are nearly dead. I’ve heard people say this unusual pattern will make it nearly impossible to prove yield damage in a field was attributable to dicamba drift. That might have been true in the past, but farmers with detailed scouting reports and accurate yield maps this season will disprove this. Overlay a map of plant tissue after off-target application with a map of yields after harvest.. If decreased yield corresponds with the areas affected by off-target dicamba damage—then the answer is pretty clear. Chemical drift caused the damage.

Likewise, if it is true that moderate dicamba drift will help the yield on non-dicamba tolerant beans this fall—I’ve heard this many times this summer—the yield map will show this correspondence. Climate Corporation's data will be able to prove this by this fall, if it is true.

Dicamba will also show us the limits of ag data platforms today. Google can tell where the flu is trending based upon online health data and where people are searching for cold medications. In theory, American farmers should be able to predict whether a particular pesticide is causing off-target problems based upon the number of complaints, satellite images, and ag data uploads. But there is no single database that collects and analyzes this information. States each have their own complaint database and farmers, retailers, and applicators are using dozens of different platforms to store ag data information, such as applications of pesticides, what crops are planted, etc.

This decentralized system of storing information won't help us predict when a certain pesticide is failing. That isn't just a dicamba issue, but a food security issue. Wouldn't it be great if we knew, based upon collective data reporting, where certain pests are problematic in the United States so that we could predict where these pests would appear next?

Big data platforms ought to be able to answer these questions before we get into the widespread mess we find ourselves in now.

But we still have a long ways to go.

One thing is certain, sorting out liability for dicamba damage is going to come from ag data platforms. Just wait and see.