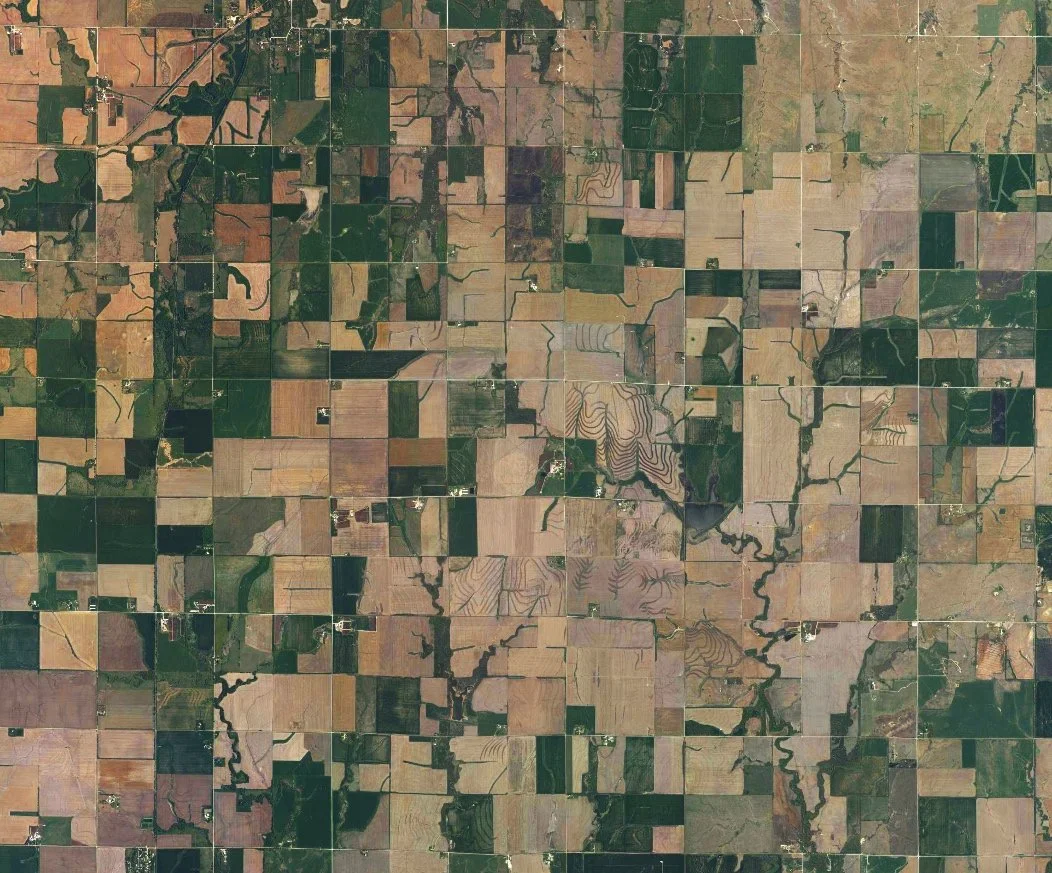

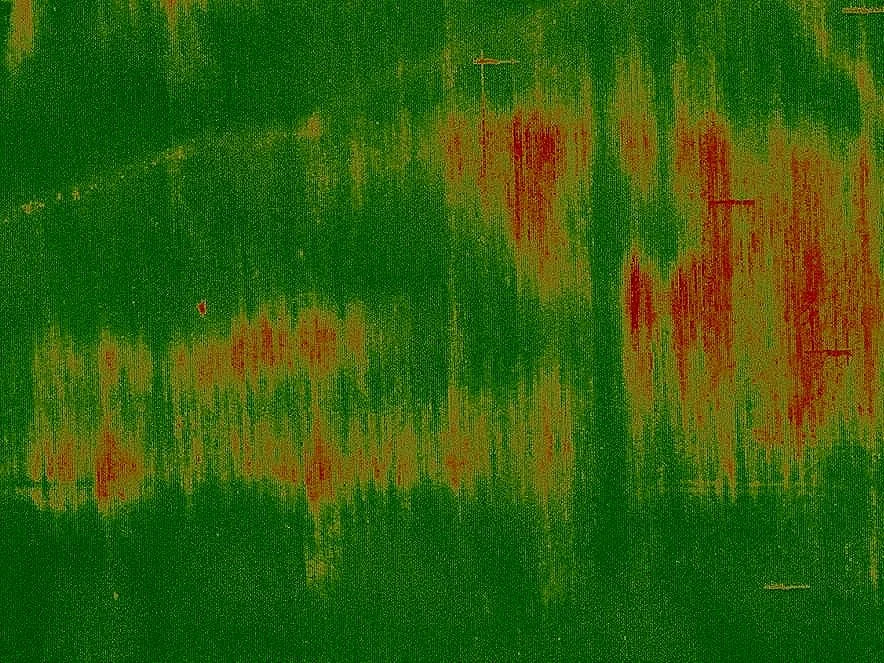

Revenue Management Software, AI, and Price Fixing Implications for Agriculture

/One of the ways that artificial intelligence (AI) has been marketed to agricultural business owners is as a tool to improve market competitiveness. AI platforms promise to deliver real time market insights in a way that humans never could, since AI has the ability to analyze much larger datasets than any single person. This post explores whether such market insight tools might actually lead to price fixing problems—illegal conduct under US law—rather than an increase in competitiveness.

What is illegal price fixing? Price fixing in the legal sense originates from the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890. Under Section 1 of the Act, in order to demonstrate illegal price-fixing conduct, a plaintiff must demonstrate that an injury resulted from: “(1) the existence of a contract, combination, or conspiracy among two or more separate entities that (2) unreasonably restrains trade and (3) affects interstate or foreign commerce.” For the purposes of this post, let’s focus on two of those elements: First, there must be some “agreement” by sellers to fix prices. Second, that agreement must be with competitors. “Competitors” are those persons or entities engaged in similar lines of business, competition for sales with similar customers.

How might AI tools create price fixing? There are many AI tools on the market already that promise market insight from data collected from various competitors in the same market. While these competitors would not agree to share their market data directly with another competitor, as that could be viewed as an agreement to fix prices, these competitors might agree to anonymously share their market data with a third-party AI tool which then shares market intelligence with its users.

An example is already underway in the real estate rental market. Using different online platforms, landlords in various cities and markets all agree to share information about their rental spaces, such as rent, vacancies, operating costs, and other information reported to a central data exchange platform. The platform uses algorithms to provide insights to landlord users, advising them that, for example, their rent is lower than average in the market space. The result—the landlord knows it can raise rent and still be competitive in the market, and a tenant that might have found a lower rent now pays the market average instead of a better deal. Is this an agreement to fix rental prices?

Are such AI pricing tools legal? We are seeing litigation on these AI-influenced rental markets start to unfold in the courts. A recent case by the Justice Department and ten states against RealPage, Inc., an online platform offering landlord “revenue management” software, has claimed that such software and its use by landlords has resulted in illegal price fixing harming tenants. As alleged by the DOJ in its Amended Complaint against RealPage:

Renters are entitled to the benefits of vigorous competition among landlords. In prosperous times, that competition should limit rent hikes; in harder times, competition should bring down rent, making housing more affordable. RealPage has built a business out of frustrating the natural forces of competition. In its own words, “a rising tide raises all ships.” This is more than a marketing mantra. RealPage sells software to landlords that collects nonpublic information from competing landlords and uses that combined information to make pricing recommendations. In its own words, RealPage “helps curb [landlords’] instincts to respond to down-market conditions by either dramatically lowering price or by holding price when they are losing velocity and/or occupancy. . . . Our tool [] ensures that [landlords] are driving every possible opportunity to increase price even in the most downward trending or unexpected conditions” (emphases added).

In fact, as RealPage’s Vice President of Revenue Management Advisory Services described, “there is greater good in everybody succeeding versus essentially trying to compete against one another in a way that actually keeps the entire industry down” (emphasis added). As he put it, if enough landlords used RealPage’s software, they would “likely move in unison versus against each other” (emphasis added). To RealPage, the “greater good” is served by ensuring that otherwise competing landlords rob Americans of the fruits of competition—lower rental prices, better leasing terms, more concessions.

Courts are wrestling with whether such rent sharing constitutes illegal price fixing because AI data sharing tools lack the traditional “agreement” between competitors. Instead, the users of the platform set prices according to the information learned through using the tool. There is no requirement to follow the market information, but is there an implied agreement if users consistently implement the platform’s suggestions? Is that enough to constitute an agreement among competitors to fix prices? We will see this issue litigated in the next few years but the answer is not clear today.

Conclusion. The outcome of the rent-sharing cases will be important for AI developers and farmers. Agricultural goods and commodities are highly competitive. Farmland rental rates in particular are extremely competitive. Use of similar “revenue management” platforms in agriculture might be viewed as anti-competitive by farmers who are used to handshake deals with landlords that do not traditionally share their rental rates. What do you think the outcome of such cases should be?