State Data Privacy Laws: The Highway to Nowhere Fast

/In 1919, a young Lieutenant Colonel named Dwight D. Eisenhower led a military convoy across the United States, from Washington D.C. to San Francisco. The excursion took 62 days and left a lasting impression on Eisenhower. After seeing the Autobahns that Germany had successfully built prior to the Second World War, Eisenhower decided to make creation of an interstate highway system a priority for his administration. In 1956, the Interstate Highway Act was passed and authorized the construction of 41,000 miles of federal highways. Traveling across America would never be the same.

Eisenhower was not the first president to want a federal highway system. FDR’s Public Works Administration worked with states to build bridges and parkways. But these one-off efforts failed to create an organized, federal approach to interstate transportation until after 1956.

As a result, it no longer takes 62 days to drive across America.

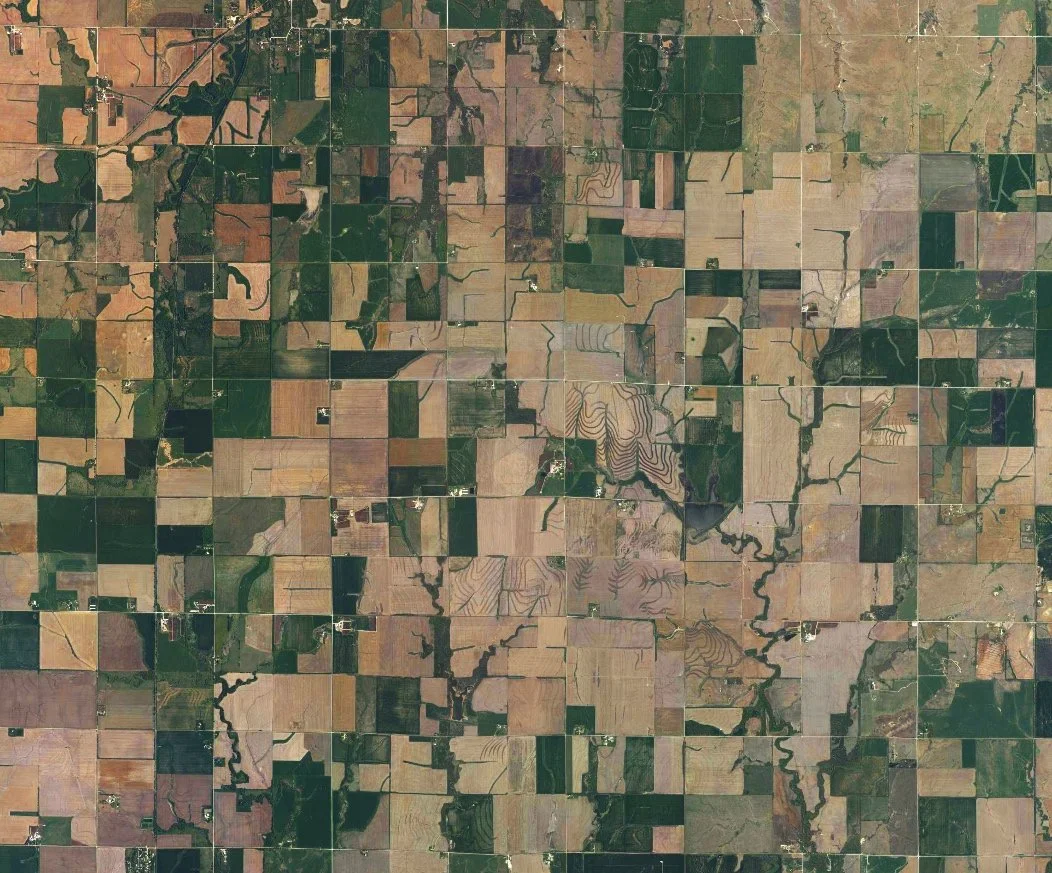

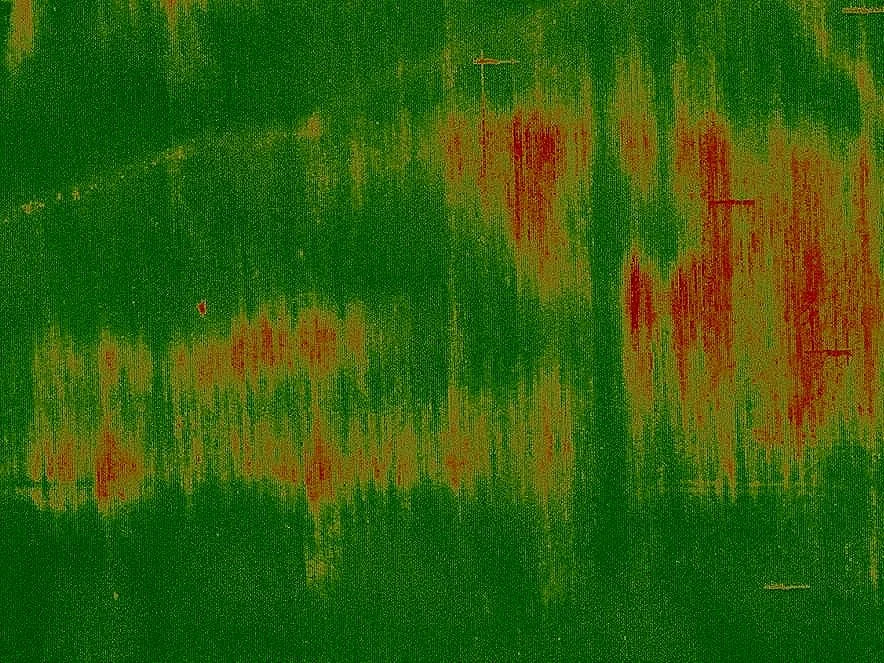

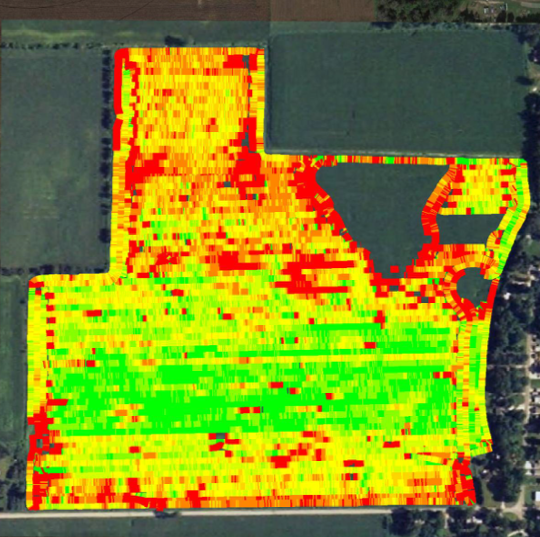

Interstate highways prior to 1956 were analogous to our online privacy laws today—well intentioned efforts by state legislatures that result in a hodgepodge of different laws. California, for example, passed the California Privacy Protection Act (CPPA). It applies to any company collecting data from at least 50,000 California citizens or deriving over 50% of their review from California. An agtech website hosted in Indiana must comply if it meets one of these criteria, even though California citizens are seeking the website out, instead of vice versa. (See previous post for more detail about CCPA).

Other states are following suit with their own laws. The National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) identifies Nevada and Vermont as states with their own online consumer data privacy laws. NCSL also details the legislatives efforts across other states, and there have been a lot of state attempts to pass bills to regulate online data collection.

Sometimes a state-by-state approach works. There have been times in history when multiple states have adopted the same uniform law. For example, the Uniform Commercial Code began as a model law and it has been adopted by nearly all states (with only a few edits here and there). That makes interstate commerce much simpler for merchants buying and selling goods across state lines.

Online data privacy protection laws, however, are not following this uniform approach. There is not a clear model data privacy law for states to adopt so we are left with one-off approaches.

State attempts to regulate online data collection overlook the two big facts about internet commerce—websites don’t care what state you are from, and web-users don’t care in which state a website is hosted (or its parent company is located). The evolving patchwork quilt of state-by-state regulations imposes an enormous burden on online platforms to ensure compliance with laws where their users are located.

Politicians often promise to reduce federal regulation. That sounds good, but if the alternative is a mismatch of state laws that impose multiple, different financial and regulatory burdens on online business, then I say no thanks. This only drives up costs for online business and consumers.

Eisenhower was right about how to fix the disorganized state highway system in the 1950s. Only a federal approach would work. The same is true for our state approaches to online data privacy protection.