An Interview about Row Crop Machinery Technology

/I was recently interviewed by Tim Roy, ASA Capitale Analytics, for The Journal of the International Machinery & Technical Specialties Committee of the American Society of Appraisers (The MTS Journal). The interview focused on ag tech in row crop machinery and is republished with permission below. *Footnotes were added by the MTS Journal.

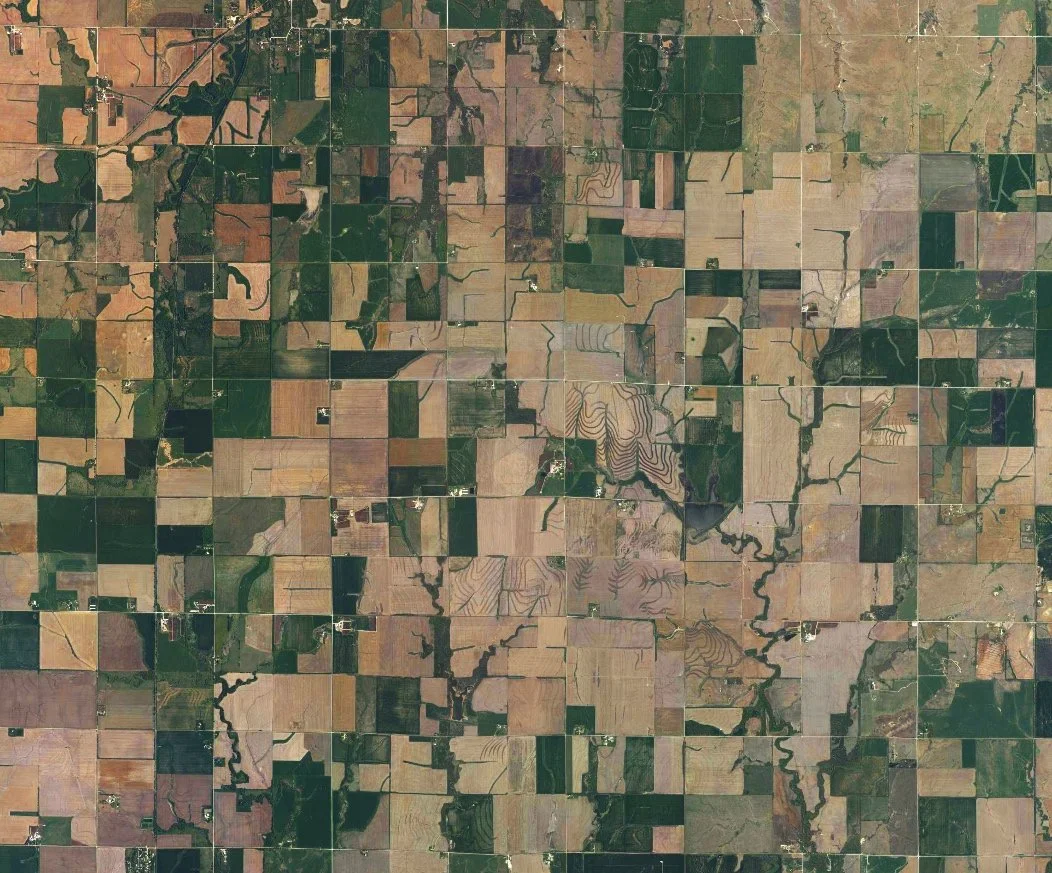

TIM ROY: “Ag tech” is a broad field. Our focus here will be technology commonly found in row crop machinery, such as combines, tractors, and planters. It seems like some type of guidance or auto operation system is now present on every major piece of machinery. Do you have a sense for whether this trend has been driven more top-down by OEMs introducing new technology, or bottom-up by user demand?

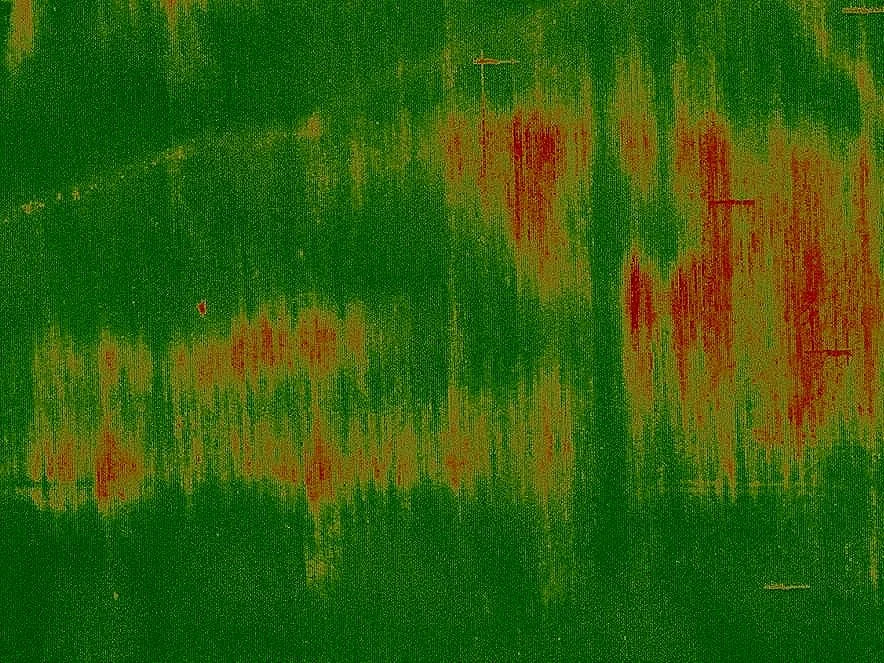

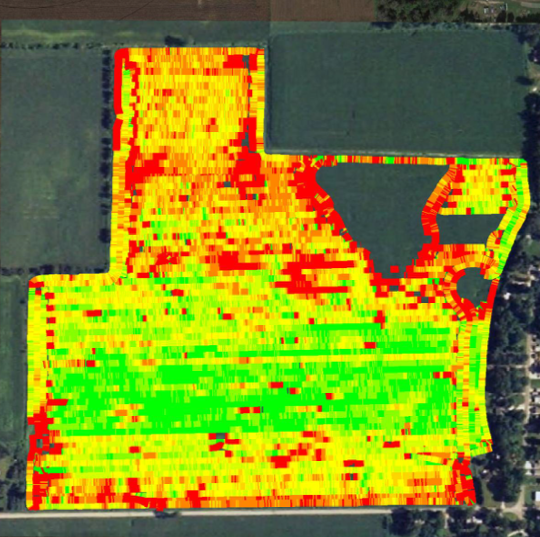

TODD JANZEN: The advancement has come from both directions. Farmers are often viewed as having a conservative mindset, but in reality, they aren’t scared to try something new. When GPS guidance systems became affordable, they had an immediate positive impact for farmers in saving time, fuel, and other inputs. That has helped encourage the market to ask for and accept other kinds of new technology, which has in turn encouraged OEMs to continue developing new technologies.

Have you seen more advancements from large OEMs or small tech companies?

Agricultural machinery has experienced a recent history similar to other heavy industries. Dozens of regional OEMs have steadily consolidated for the last century, leaving only a few major players.* This contributed to somewhat of a slow evolution in technology, as large corporations offered incremental advancements and focused on protecting their market share as opposed to investing in risky – but potentially revolutionary – technology.

Tech startups backed by venture capital started really shaking up the marketplace in the past 10-20 years. Early guidance systems and automation technology were aftermarket accessories. Major OEMs have responded to user demand by buying the tech or developing their own versions of it, and integrating the systems directly into their new models. The OEMs have also created venture capital groups to fund new tech startups under their own umbrellas.

As of yet, there is no “Tesla” of tractors which presents a real potential threat to the major row crop machinery OEMs. But otherwise, the pattern of outside innovation and OEM response has been similar to auto manufacturing.

*John Deere leads the North American row crop machinery marketplace, followed by CHNI (New Holland and Case IH, among other brands) and AGCO (Challenger, Massey Ferguson, et al). (Sources: Market Research Reports; Statista; Markets Insider)

It is easy for us as appraisers to spot the interfaces and control boxes on the machinery itself. What other kinds of investments are required that we may not see when inspecting machinery?

The modern systems are mostly software and cloud-based. There may be servers and other hardware in the office that sync to the hardware on the machinery, but the major investment will often be in the software and system upgrades. Perhaps the more significant support investment is being required of machinery dealerships, which now need to support the technological as well as the mechanical side of the machinery. This requires a different set of tools, employees, and training programs than they traditionally employed.

There was a popular news story out of Minnesota last year about rising auction prices for 40-year-old “pre-tech” John Deere tractors.* You blogged about the story and expressed your opinion that farmers were not necessarily rejecting new technology, but rather did not feel that the incremental advancements offered by OEMs in the past few decades justified the high price tags on new machinery. Do you still hold that opinion?

Yes I do. Farmers all want higher yields and more efficiency. But in some circumstances – particularly for smaller operations – the skyrocketing price of new machinery has not been justified. A pre-tech tractor is easier and cheaper for the farmer to maintain in-house, and aftermarket guidance systems can provide modern efficiencies without a full OEM integration. Like most tech, these kinds of systems have become very affordable.

However, I do believe that the trend will run its course eventually. It will get harder to find parts for the old machines over time, and things like electrical hookups for new attachments and implements will become ever harder to retrofit to old machinery. At some point the costs of new machines will be justified by their efficiencies and ease of use, even for small operators.

*Belz, Adam. "For tech-weary Midwest farmers, 40-year-old tractors now a hot commodity: Tractors built in 1980 or earlier cause bidding wars at auctions." StarTribune [Minneapolis], January 5, 2020.

The “Right to Repair” movement has been a part of this conversation as well. John Deere in particular has been criticized for not allowing farmers to modify or maintain newer machinery without dealer involvement. Do you have a sense of where this conflict is headed?

John Deere has caught a lot of flak, but in reality this is a society-wide issue. Elon Musk said that a Tesla is not really a car but rather “a sophisticated computer on wheels.” We could say this about many of the items we use every day – cars, phones, appliances, and so on.

I sense that eventually it will become a moot issue. Do you really want to hack into your iPhone and risk ruining it? How many people want to repair their own car anymore? Farmers who make major investments in high-tech machinery will probably come to feel the same way.

Do large consolidated farms care about the “Right to Repair” movement? Or is this an issue only among smaller independent operators?

Of course I can’t speak to every situation, but my sense is that in general, larger operations are going to view machinery as a regular input cost as opposed to an owned asset. They will be more likely to lease machines or cycle through them quickly in order to get the latest efficiency upgrades with new machinery, as well as to reduce downtime. The largest operators will keep system techs on staff just like they keep mechanics on staff. They will have close relationships with dealers who will help resolve any issues their machinery.

Smaller operators may be more likely to look at machinery in the traditional sense: as an owned asset to be purchased, paid off, and maintained over a long duration. It seems logical that these operators are more likely to want to have the right to maintain and modify their own machinery.

Instead of continuing to pay top dollar for 40-year-old tractors, I would not be surprised to see farmers turn to “open source” control systems, small electric tractors, and other affordable new tech machinery built specifically for the next generation of tech-savvy independent operators.

As we’ve already touched on, farming is transitioning (like most industries) into a marketplace of very large and very small operators. Where does tech fit into this transition?

This transition is being caused by many factors, including government policy, global trade economics, land value trends, and shifting generational perspectives about farming. Tech is integrated into every one of these factors, and into every aspect of farming and farm ownership, just like it is integrated into everything else in modern society. Farms of any size can operate more efficiently with less labor and higher yields than ever before. In some instances, new technology helps smaller operations become competitive with larger ones, such as robotic milking machines that keep small dairies in business. In other areas, new technology benefits larger operations that can afford the initial investment. Tech in and of itself is not really causing this divide.

You recently wrote about “swarm farming” – fleets of small field robots replacing traditional large machinery. Is this something that you expect to see in practice in the near future?

Farmers are usually willing to give new ideas a try. Swarm farming has potential for many reasons. It is easy to scale up and down for different operation sizes. It reduces man-hours in the field. It can be extremely precise – one robot can head out to apply inputs to a small area without disturbing the rest of the crop. A broken down unit does not stop the entire activity since other units continue to operate. Compared with big and heavy machinery, small and lightweight robots don’t compact the soil or sink into the mud as much. There are many potential advantages.

However, my point was not so much that any one technology is going to become widespread. My point instead was that the next generation of farm machinery might not look anything like what we’re used to. Many of the current visions for autonomous tractors coming from major OEMs look pretty much like a regular tractor without a cab. Is this practically necessary, or is this just meant to ease the transition for operators from a psychological standpoint? Perhaps the next generation of farm machinery will represent a completely fresh operational philosophy.

This article was originally published in The Journal of the International Machinery & Technical Specialties Committee of the American Society of Appraisers, Vol. 37, Issue 1, Summer 2021. Special thanks to Tim Roy for taking the time to conduct the interview and put this article together.