Making Hay: A History of Hesston Corporation

/I love reading corporate histories, especially when they are about agribusiness. I just finished Factory on the Plains: Lyle Yost and Hesston Corporation, which tells the story of Hesston farm equipment from its humble beginnings through the eventual consolidation with AGCO. Having spent much of my teenage years cutting hay in a Hesston Swather, I found this history particularly interesting.

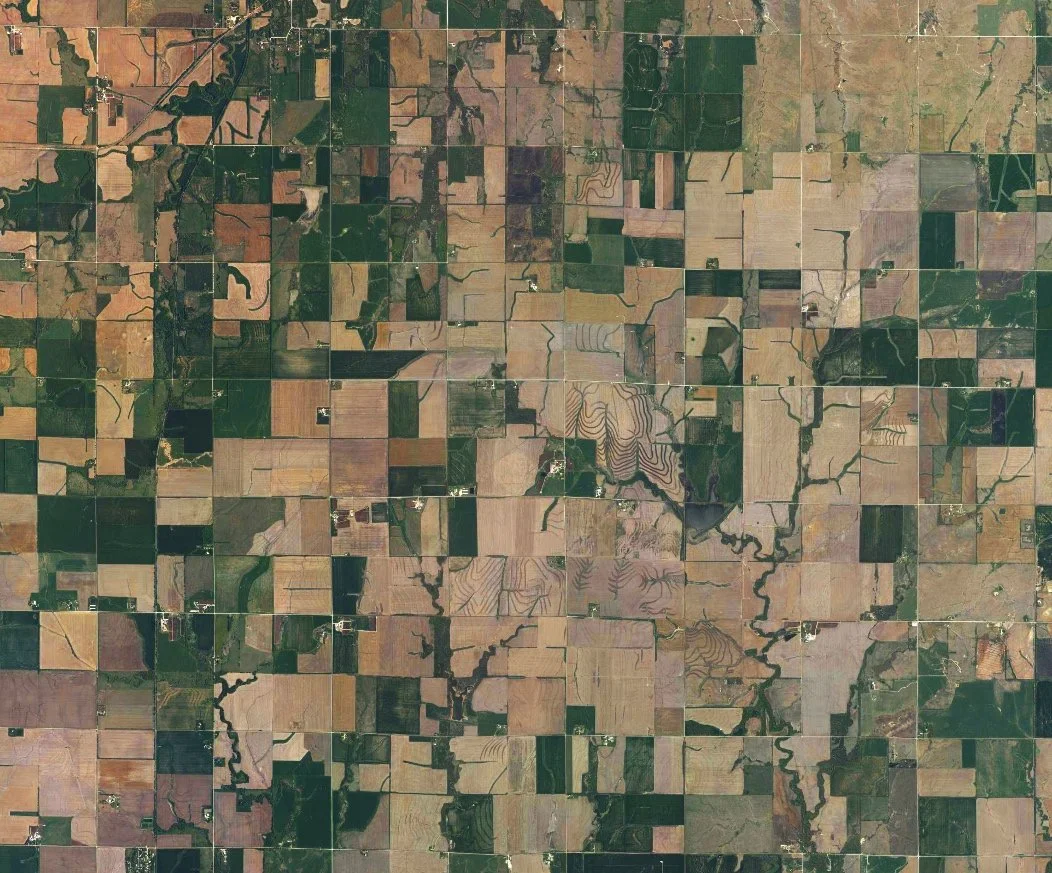

Hesston 6600 Swather

Hesston Corporation began almost by accident. Lyle Yost, a Kansas farmer and early custom harvester, was frustrated by the long unloading times required by 1950s combines that used gravity flow to empty their grain bins. With the help of local welder, he fabricated an unloading auger to mount onto the side of his combine and speed up unloading. It worked, and he was quickly flooded with requests from other combine owners who wanted to buy unloading augers. He hired a number of local farmers to fabricate augers when not busy on the farm, and Hesston Corporation was born.

In a few years, all combine manufacturers would incorporate unloading augers into their designs, and Hesston sought new ways to help farmers. This theme—increasing the efficiency of farming—continued to drive the purpose of the company. The company acquired the design rights to a hay windrower—the swather—from an Iowa farmer who had designed and built his own hay machine. Production was moved to Hesston, Kansas, and upscaled. The swather was a hit, revolutionizing how hay was cut and cured for thousands of farmers and ranchers. Hesston continued to focus on haying equipment for the next two decades.

Hesston later branched into other market segments by acquiring smaller companies, improving their products, and streamlining production. By the mid 1970s Hesston was the ninth largest farm equipment manufacturer and the United States’ leading manufacturer of haying equipment. It sold haying equipment in across the globe.

However, in 1976 the agricultural market entered a long, downward trough that would continue for nearly a decade. Farmers decided to hold onto equipment longer and dealer lots were filled with equipment that wasn’t selling. Hesston avoided bankruptcy by selling a controlling interest in the company shares to Fiat Corporation of Italy. Yost and other founders retired or lost their board seats. Hesston would never again be controlled by its founders. Today, it is a subsidiary of AGCO.

Hesston’s story tells a similar story to other farm equipment companies (John Deere, Kinze, Vermeer). These companies were started by entrepreneurs who wanted to solve specific problems on the farm. Demand for their solutions pushed them to start companies to mass produce their fixes.

In a world where venture capital often looks for problems to solve with existing solutions, it’s refreshing to read about how one entrepreneur did the opposite, working hard to find solutions to farmers’ problems.