Dairy Farm PFAS Contamination

/A New Mexico dairy farmer has been in the news lately, and it isn’t good news. Art Schaap is dumping 15,000 gallons of milk each day, had to let 40 of his employees go, and plans to terminate all 4,000 of his cows because 7 of his 13 wells have been contaminated by toxins called per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) that entered the groundwater at nearby Cannon Air Force base. Now Schaap is stuck with contaminated milk, beef, and crops he cannot sell.

According to various reports, the Department of Defense has known for some time of the dangers PFAS can cause. PFAS are a group of man-made chemicals that includes PFOA, PFOS, GenX, and many other chemicals. PFAS are persistent in the environment – meaning they don’t break down and can accumulate over time. This makes them especially dangerous for humans and farm animals where repeated ingestion leads to bioaccumulation in the body. PFAS have been used in manufacturing in the US since the 1940s. Airports and military installations that use firefighting foams are the main sources of PFAS at Schaap’s dairy.

I was in Washington DC last week with the AgriInstitute Leadership Program. We met with the EPA, Farm Bureau, the Environmental Working Group, and many other agencies. PFAS were a common topic of conversation in DC. The EWG is focused on PFAS right now and has identified and mapped 106 military sites in the U.S. where drinking water or groundwater is contaminated with PFAS at levels that exceed the EPA’s health guideline. When the Air Force tested Schaap’s water on Aug. 28, 2018, the military immediately began delivering bottled water to the family home. One of Schaap’s wells tested at 12,000 parts per trillion (ppt), or 171 times the EPA’s non-enforceable health advisory level of 70 ppt.

On February 14, 2019, the EPA announced a new PFAS Action Plan. According to the Plan, by the end of 2019, the EPA will propose a regulation to create a Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) for PFAS in drinking water. This is the first step in regulating PFAS in drinking water (unlike the 70 ppt guidance level, which does not have the force of law). Critics say waiting until the end of the year is taking too long. Indiana’s Department of Environmental Management currently is conducting PFAS “environmental oversight” with the Department of Defense on four military installations in Indiana. At least 30 sites in Michigan have confirmed PFAS contamination. Ohio has had at least five PFAS contamination sites.

The end of the year is, of course, too late for New Mexico dairy farmer Art Schaap. The Food Safety Inspection Service said his cows are adulterated, so he cannot sell them for beef. The milk produced by the cows is impacted and not sellable. Schaap filed a claim against the Air Force and manufacturer of the product that used the chemical. The State of New Mexico has filed a lawsuit against the US Air Force alleging the military isn’t doing enough to contain or clean up PFAS below two Air Force bases, including the one near Schaap’s dairy. A copy of the lawsuit is available here.

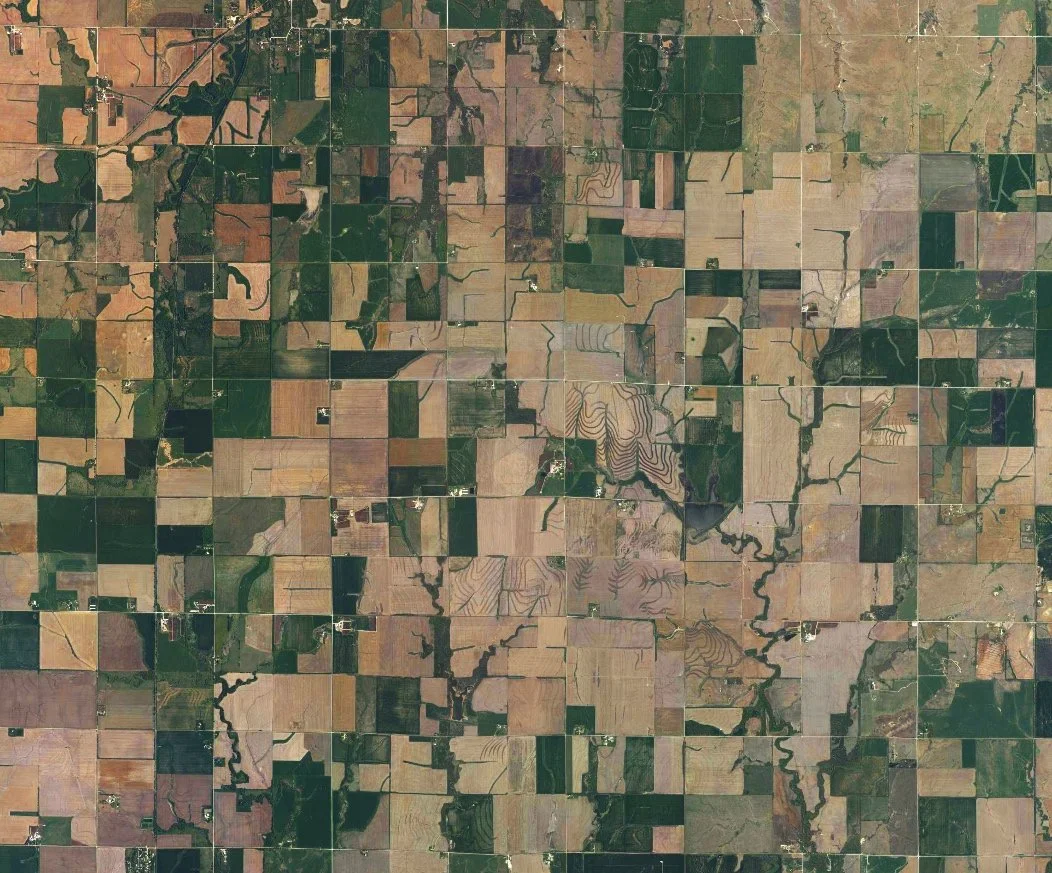

Schaap is the first dairy farmer to feel the pain of the PFAS problem, but he likely won’t be the last. New Mexico news stations report PFAS is spreading slowly in the Ogallala Aquifer, the biggest aquifer in the U.S., which spans parts of eight states. Dairy farmers — and all citizens — should pay attention.